*Ceasefire ‘Broken’ Before It Began

The Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement signing ceremony on Oct 15 was Thein Sein’s big chance to add some much-needed credence to the national elections to be held next Sunday.

But despite Thein Sein and Gen Mutu Sae Po’s optimism, not everyone is convinced the NCA will bring stability to the country. In fact, ethnic groups say fighting continues unabated, killing civilians and displacing thousands.

Hard-hitting public statements from Karen organisations opposed to the deal have condemned Gen Mutu and his negotiating team. A coalition of international and regional Karen groups also sent open letters to the KNU leader expressing alarm over its decision to sign the NCA.

On the eve of the ceasefire signing, the Karen National Liberation Army issued a statement making their position clear: They would never give up their cause.

Even the KNU’s vice-chairwoman, Padoh Naw Zipporah Sein, who led its senior negotiation team, knocked back an invitation to attend the ceasefire ceremony from President’s Office Minister Aung Min.

Her letter diplomatically thanked the minister for his invitation but said she could not attend, because “fighting continues” and “civilians are afraid and do not have security”. “I have no strength to attend the NCA ceremony,” she said.

The United Nationalities Federal Council, an alliance of ethnic armed groups, issued a statement saying military offensives had been launched against groups excluded from the deal — the Shan State Progress Party, the Palaung State Liberation Front and the Kachin Independence Organisation.

‘RIDICULOUS’ PACT

Sai Hor Hseng, a spokesman for the Shan Human Rights Foundation, told Spectrum there has been daily fighting as the government cracks down on those not involved with the NCA. He said an offensive involving more than 10 Myanmar army battalions was launched in Shan territories on Oct 6, killing and forcing locals from their homes.

“There’s been fighting every day, including on the day of the NCA signing,” he said. “More than 4,000 villagers are now displaced. Helicopter gunships and jets were used on Oct 25 in the Ta Sarm Boo and Nawng Ked areas. Villagers are terrified.”

Maj Gen Nerdah Bo Mya, head of the Karen National Defence Organisation, dismissed the NCA as “ridiculous”.

“This is not a nationwide ceasefire, how can it be? It’s ridiculous when most of the Kachin, Shan, Mon and Karen’s biggest resistance groups were deliberately excluded by the government and are now being attacked by the Burma army.”

He said the government’s strategy was simply to get the NCA signed before the national elections.

“It didn’t matter that only eight out of 17 of the armed groups signed, it didn’t matter that there is still fighting with four armed groups. They needed the NCA signed.”

The general is sceptical the forthcoming polls will be either fair or free.

“How can they say it’s a democratic election when the military has an automatic 25% of the seats — is that fair?

The military-backed government won the last election and they will win again, because they control the electoral process. We already know that thousands of names have disappeared from electoral rolls. The government will deny ethnic people their right to vote by claiming our areas are too dangerous.”

The Burma Electoral Union Commission has already closed polling stations in 150 Karen and 212 Kachin areas, plus across five entire townships and another 56 polling districts in Shan state.

The general predicted the government will target more ethnic resistance groups who did not sign the NCA after the election.

“We know they are preparing to attack the Kokang, the Kachin and the Karen Army’s Brigade 5,” he said. “They will win the election and that will legitimise their actions against ethnic people and the resistance groups — Burma will have a military dictatorship.”

A DIFFERENT WORLD

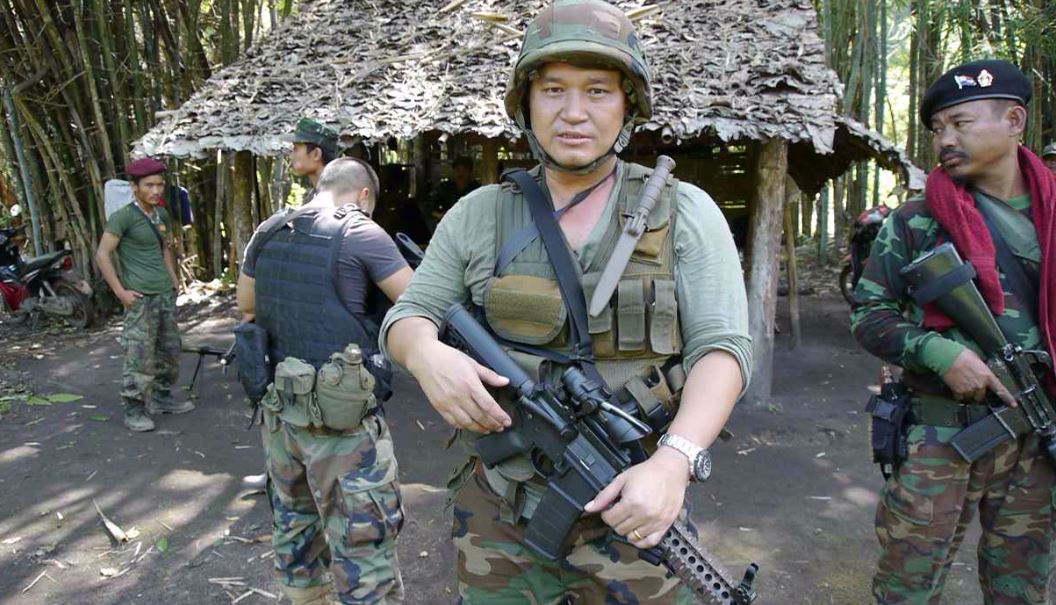

The bamboo and wood buildings in the KNDO jungle camp are a long way from the pomp and fanfare surrounding the ceasefire ceremony in Myanmar’s capital, Nay Pyi Taw.

Maj Gen Nerdah Bo Mya is the son of the legendary Karen leader and military hardman General Bo Mya, who fought various Myanmar military regimes for more than 50 years before his death. He said he will not give up his father’s struggle until the government accepts a ceasefire with all ethnic armed groups.

“We respect the legacy of our leaders — Ba U Gyi, Mahn Ba Zan, my father, and all our soldiers and villagers who sacrificed so much. How can we now accept a nationwide ceasefire that excludes the other ethnic groups?”

The mountains surrounding the general’s headquarters are lush from the wet season and heavily armed soldiers gather around him as he prepares for a river trip.

The general cannot hide his disdain for the international community and “Myanmar experts” who he says constantly distort the “Burmese narrative” and put pressure on ethnic groups for their own political and business interests.

“We are not children. Treat us with respect and dignity,” he said. “We know our lands are rich with natural resources. We have gems, forests, gold, oil and rivers for hydropower. Control of these resources is what is driving the government. If they want genuine peace, they should start by removing the Burma army from our lands and stop the fighting in Kachin and Shan states.”

A group of heavily armed Karen soldiers pack into a large long-tail boat, physically and mentally hardened by years of jungle and mountain warfare. Slogans and motifs reflecting their freedom struggle are inked onto their chests, legs, arms, hands and fingers.

The general said the Karen want much more than a nationwide ceasefire: “We want our freedom, we want our rights, we want an equal political say in our affairs, we want our territory and we want our resources for our people.”

A uniformed Karen soldier interrupts to say they are fighting a “just cause”, and to make a dig at the Karen leaders who signed the pact with the government.

“We are not sitting around in big hotels talking about who can sign the ceasefire while being insulted by the government,” he said. “Karen soldiers don’t get paid. Look around, we are here to protect our people, our motherland. We will continue to do so, even it means fighting another 60 years.”

The general picks up on the same theme. His voice drops to a whisper as he critiques KNU leaders involved in the deal: “This ceasefire will be no different. It is already full of broken promises — I feel sorry for those leaders who don’t learn from the past — they keep making the same mistakes.”

He stresses the Karen do want peace with the government, but any pact must do more than “just please the international community” because “the Burmese government continues to portray us as ungrateful, uneducated children unable to take part in political discussions”.

The government’s strategy is simple, he said. “This is about divide and rule. Why call for a nationwide ceasefire, when they keep fighting? If we all signed they would have to think about having real political discussions — that’s why they resist.”

By excluding the majority of ethnic armed groups from signing the NCA, the government has given itself many years to avoid sharing power with ethnic people, he said.

“The government has used this strategy for years. It had a 17-year ceasefire with the Kachin while it fought the Karen. Now it wants a ceasefire with the Karen while it uses helicopter gunships and jets to bomb the Kachin. By having these ‘wars’ it can implement its plans to ‘Burmanise’ and militarise ethnic lands in order to steal our resources.”

NO POWER SHARING

Bawmwang La Raw, president of the Kachin National Organisation and an executive member of the United Nationalities Federal Council, says continued fighting in the north of Myanmar has already displaced more than 200,000 civilians.

“Travel is now severely restricted, civilians are unable to move. Aid for the displaced people is restricted — medicine is not getting get through.”

The government is still “using helicopters and jets to intimidate civilians by flying over villages”, he added, questioning why the international community is accepting the supposed ceasefire while fighting is still raging.

“Against this background, how can anyone call this a real nationwide ceasefire agreement?” he asked.

It is not in the government’s interests to address the political aspirations of ethnic people, Bawmwang La Raw said. “They don’t want a real ceasefire. The government strategy is to use this term to try to look like they are addressing ethnic issues, but they don’t want to share power.”

He argues the continued use of heavy weapons, helicopter gunships and jets in civilian areas is a true indicator of how the government works.

“In 1994 we signed a ceasefire, 20 years later we are still fighting,” he said. “They cheated us. We wanted political dialogue and a signed agreement. They promised us they would commit to political dialogue and the signing of an agreement when a proper elected government was in place. After the elections we tried again and they attacked us.”

Bawmwang La Raw points out that in June 2011, a 17-year ceasefire between the Myanmar army and the Kachin Independent Army disintegrated into a full-scale conflict.

“They want a quick ceasefire that they can hold up and say, ‘Look, we tried to have a ceasefire, but the ethnics broke it again’. This is their tactic,” he said.

“Kachin State is highly prized by the government — they want our jade deposits, timber and to control our border with China. This is important because it is China’s route through Kachin that allows them passage to the Bay of Bengal.”

Bawmwang La Raw said constant Myanmar army offensives mean “displaced people can’t go back as their homes”.

“Burmese soldiers now occupy their villages. When the soldiers abandon the villages they will landmine them. Against this backdrop the nationwide ceasefire is a farce and meaningless for us.”

He is critical of the armed groups who signed the ceasefire. “By signing the NCA the eight ethnic groups have legitimised the Burma army offensives against ethnic people. It says to the world that it is OK to wage war against us.”

CALL TO UNITE

In a leafy garden in a northern Thai city, Bawmwang La Raw sits across the table from David Tharckabaw, head of the KNU’s Alliance Affairs Department. Both are veterans of Myanmar’s lengthy civil war.

David Tharckabaw warns that ethnic armed groups must not split under this new phase of pressure from the Myanmar government and the international community.

“It is important we remain united, but it is not easy while international support is now behind the Burmese government. If we can be united, Burma will change for the better. It is unfortunate that some of our leaders have been corrupted — they are thinking about their own interests not the interests of the ethnic people.”

He said he supports a nationwide ceasefire that includes all ethnic armed groups, but was dismayed at the lack of respect paid to the ethnic leaders who attended recent peace talks.

“I support a ceasefire that will give us real peace,” he said. “But I am against this agreement, because it is not going to lead to real peace. There was no equality for the ethnic leaders involved in the talks. There is no clear political road map and there is no inclusiveness.”

David Tharckabaw also suggested the NCA was a government strategy to get its hands on land controlled by ethnic groups, and said the fact the KNU had signed the truce does not mean the Karen revolution is over.

“Not all the ethnic stakeholders were included in this process,” he said. “This NCA is for development that will benefit only a few people.

“This is not the end of the Karen political struggle. There are 10 million Karen people in the country. They will get involved in the struggle for our freedom, equality and self-determination; the right to develop ourselves.”

He cited fresh military offensives as an indication of the government’s real intent.

“Troops have been fighting in the DKBA, Kachin, Kokang and Paloung areas, so we are questioning the sincerity of the government. They are carrying out a brutal war against some ethnic groups while pandering to others in talks.

“We want political rights, peace and stability,” he added. “Only after that can we have real development. Our political rights are very simple. We want equality and the right to develop ourselves. No oppression, or domination by the central power. We should have autonomy. We are fighting against the exploitation of our people and our natural resources.”

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

David Tharckabaw is keen to point out that ethnic groups could make life difficult for the government if they joined forces.

“Altogether, ethnic groups form nearly 70% of the population. If we are united, we can gain our political rights in a short time. That’s why the government has tried to divide ethnic unity since independence.

“After more than 60 years of struggle, we ethnic people should realise we have to work together, otherwise we will hang separately.”

Desmond Ball, a professor in the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at Australian National University, agreed that factional splits among armed ethnic groups reduces their political effectiveness.

“It’s in their own interests to help each other,” he said. “If one falls, it will hurt them all. Once the regime gets legitimacy from the ballot box it will be used to crack down on the ‘troublesome’ groups.”

Mr Ball suggested the government’s offensives against individual ethnic armies could have the unintended consequence of forcing them together. “Ceasefire groups could join those already fighting and there could be armed resistance on a scale not seen for decades,” he said.

The academic said that while some reforms in Myanmar have been encouraging, the situation in ethnic areas is likely to get worse.

“Local companies, often owned by army personnel and backed up by army units, will unquestionably move to displace ethnic peoples from land that might hold valuable minerals, or farmland expanses that can be used for commercial rice, rubber and corn plantations, or areas usable for important and profitable infrastructure projects,” he said.

Mr Ball said this type of situation is typical in fledgling democracies.

“There’s enough evidence that as countries emerge from civil war, one of the features of early democratisation is to get rid of the ethnic minorities and take over their land and property,” he said.

“Burma is still a military country and all ethnic people know about the abuses, including land expropriation and forced displacement of villagers committed during major investment projects.”

DESPERATE FOR PEACE

Mai is a community worker from northern Shan state and has seen first-hand the devastation that has displaced villagers.

“Villagers are trapped by the fighting between armed ethnic groups and government forces,” he said. “There has been continuous fighting since 2011. People can’t get health care, can’t travel and can’t attend to their fields or crops.

“We live on the China-Myanmar border and there are four armed groups fighting the Burma army — the Kokang, TNLA, Kiachin and the SSA-Nth. The people desperately want peace, but how can they get it?”

When fighting erupts, villagers take refuge in the nearest monastery, church or in the jungle.

It has taken Mai five days of tough travel to get to a border town with Thailand. His shy laugh belies deep concern that his visit to the border could be misunderstood.

“We fear the army will arrest us for supporting one of the armed groups. The army has surrounded the villages, so people can’t move. It’s worse for the women and children. The men run to the hills or jungle, but the women have to stay in the villages.”

Mai said control of the profitable drug trade in northern Shan state is a huge factor in the fighting. He accuses the Myanmar army of being involved in the drugs trade, alongside a government-sponsored village militia in the Nam Kham area.

“The militia is run by a member of the USDP and under the control of the army. It produces opium and methamphetamines. When the TNLA tried to arrest and to stop the drugs, the army stepped into protect its militia. It’s crazy, we read and hear that Burma is all OK now, yet we have soldiers ruining our lives and face fighting every day.”

DOOMED TO FAIL

Naw K’nyaw Paw, spokeswoman for the Karen Peace Support Network, said it will be impossible to “end almost 70 years of armed conflict without having every armed ethnic organisation included in the signing of the NCA”.

The coalition of community organisations is yet another group that believes the government intends to create division by signing a peace deal with some groups while excluding others.

“It will mean more conflict by creating a rift between those who have signed and those who have not,” she said.

“Groups that are not included in the NCA will continue to form alliances and fight against the Burma army.

“Unfortunately many ethnic leaders, despite knowing the history, took the risk of signing the ceasefire. If they had been able to stand together throughout, the ethnic voice would have been a strong voice in the political reform process.”

Her big fear is that “development projects” will wreak havoc in ethnic villages, forcing communities from their land.

“We are concerned development will be prioritised over political resolutions. This will bring land confiscation, pollution and environmental destruction.”

She said the army has already increased its numbers and reinforced military camps in ethnic areas to protect powerful business interests connected to the government.

“Only the elites, military cronies and business people are benefiting from all this development while the poor and local people pay the price,” she said. “This is not fair and this too will create more conflict.

“They want to see one race, one country and one army. This is their priority above the needs and rights of the indigenous people of Burma.”

She added that women must be included in peace talks, warning the innocent victims in the conflict are “pregnant women, newborn babies, mothers and elderly people”.

“We have asked the Myanmar Peace Committee to apply the UN Security Resolution on women’s participation, and we have demanded that international donors also apply pressure,” she said.

“But as usual, we are told that this is not the time. Meanwhile women in the ethnic conflict areas have to survive, care for their families, deliver babies and suffer so much. Women should be at the heart of any peace-building or ceasefire negotiations.”

To Naw K’nyaw Paw, the army’s ultimate goal is to obliterate Karen resistance.

“We have to maintain and protect our people and our ancestral land. We have a duty to do so,” she said.

*This article first appeared on Bangkok Post on 1 November 2015.